Why do prediction markets need automated market makers?

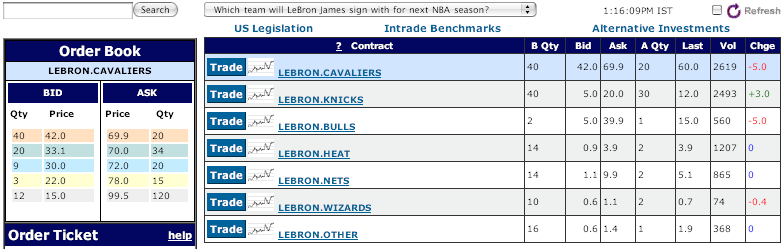

Here’s an illustration why. Abe Othman recently alerted me to intrade’s market on where basketball free agent LeBron James will sign, at the time a featured market. Take a look at this screenshot taken 2010/07/07:

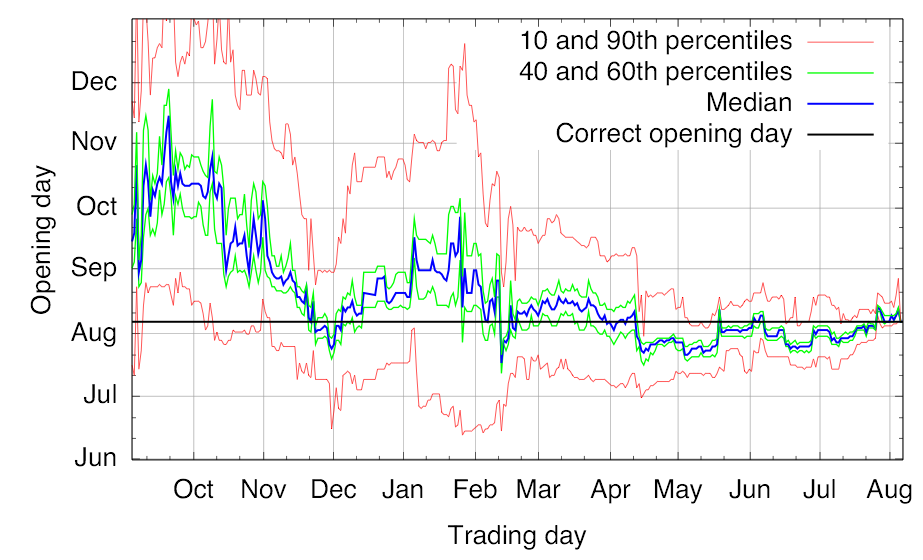

The market says there’s between a 42 and 70% chance James will sign with Cleveland, between a 5 and 40% chance he’ll sign with Chicago, etc.

In other words, it doesn’t say much. The spreads between the best bid and ask prices are wide and so its predictions are not terribly useful. We can occasionally tighten these ranges by being smarter about handling multiple outcomes, but in the end low liquidity takes the prediction out of markets.

Even if someone does have information, they may not be able trade on it so may simply go away. (Actually, the problem goes beyond apathy. Placing a limit order is a risk — whoever accepts it will have a time advantage — and reveals information. If there is little chance the order will be accepted, the costs may outweigh any potential gain.)

Enter automated market makers. An automated market maker always stands ready to buy and sell every outcome at some price, adjusting along the way to bound its risk. The market maker injects liquidity, reducing the bid-ask spread and pinpointing the market’s prediction to a single number, say 61%, or at least a tight range, say 60-63%. From an information acquisition point of view, precision is important. For traders, the ability to trade any contract at any time is satisfying and self-reinforcing.

For combinatorial prediction markets like Predictalot with trillions or more outcomes, I simply can’t imagine them working at all without a market maker.

Abe Othman, Dan Reeves, Tuomas Sandholm, and I published a paper in EC 2010 on a new automated market maker algorithm. It’s a variation on Robin Hanson‘s popular market maker called the logarithmic market scoring rule (LMSR) market maker.

Almost anyone who implements LMSR, especially for play money, wonders how to set the liquidity parameter b. I’ve been asked this at least a dozen times. The answer is I don’t know. It’s more art than science. If b is too large, prices will hardly move. If b is too small, prices will bounce around wildly. Moreover, no matter what b is set to, prices will be exactly as responsive to the first dollar as the million and first dollar, counter to intuition.

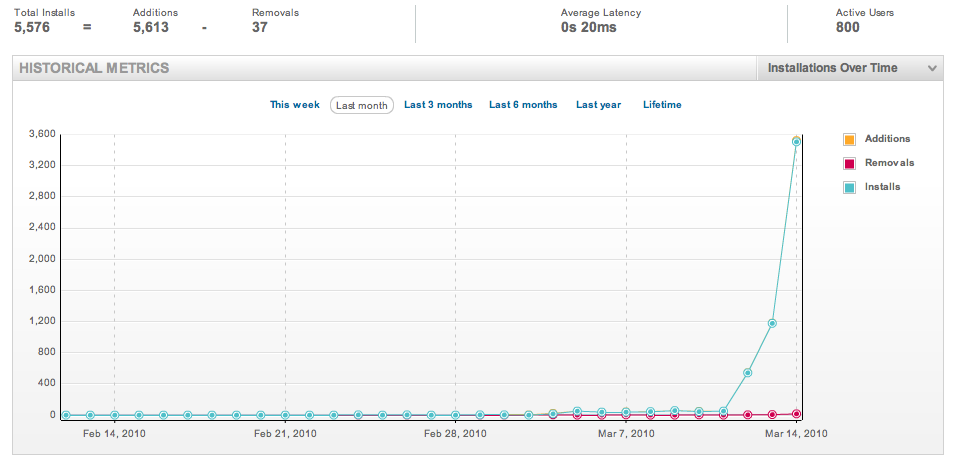

Our market maker automatically adjusts its level of liquidity depending on trading volume. Prices start off very responsive and, as volume increases, liquidity grows, obviating the need to somehow guess the “right” level before trading even starts.

A side effect is that predictions take the form of ranges, like 60-63%, rather than exact point estimates. We prove that this is a necessary trade off. Any market maker that is path independent and sensitive to liquidity must give up on providing point estimates. In a way, our market maker works more like real bookies who maintain a vig or spread for every outcome.

The market maker algorithm is theoretically elegant and seems more practical than LMSR in many ways. However I’ve learned many times than nothing can replace implementing and testing a theory with real traders. Final word awaits such a trial. Stay tuned.